Six Pack Abs In The New Year

Our topic of study for this school year is well known muscles groups. Last month, we looked at the hamstrings, examining the different muscles that compose the group and how these muscles act on the back of the leg and even the posture. If you missed it, you can catch up here.

This month we are going to focus on another group of muscles that also gets attention, the hip flexors. There are multiple muscles that make up the hip flexor group. They are the Tensor Fascia Lata (TFL), Rectus Femoris, Satorius and the Iliopsoas. Even the adductors (a whole other group of muscles on the inner thigh requiring a discussion for another time) have the potential to assist in hip flexion.

Of the hip flexor group, three of the muscles start on the front of the hip bone. They are the TFL, the Rectus Femoris and Satorius. As they attach to the front of the hip bone, these muscles can only flex or bring the leg to 90 degrees. They obviously cannot pull the leg higher than hip bone level as that is where these muscles begin.

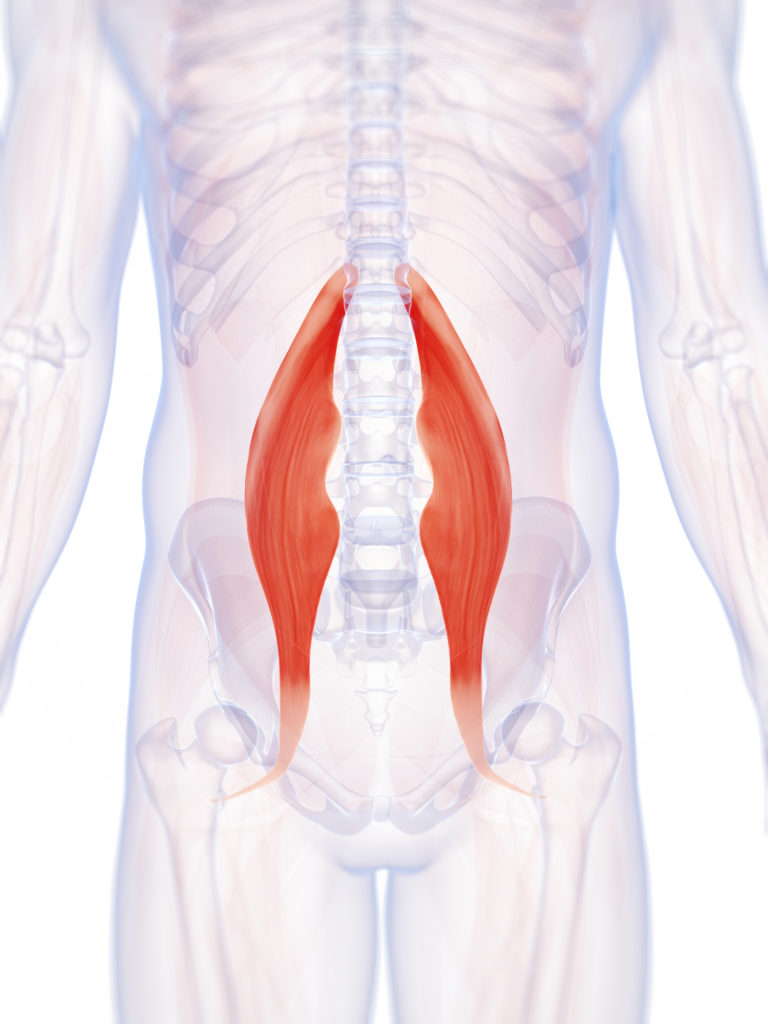

Which leads to the iliopsoas, the hip flexor muscle I particularly want to highlight. The iliopsoas is composed of the psoas major, psoas minor and the iliacus. Interesting to note that not everybody has a psoas minor. The psoas major and minor have the same function so for those without a psoas minor they may never know it.

The psoas major starts deep in low back at the (lumbar) spine and runs across the front of the hip bone and attaches onto the leg (femur). The iliacus starts inside the hip bone and then runs along with the psoas to attach at the same spot on the leg bone.

As it has a higher starting point, the psoas major can bring the leg into hip flexion past 90 degrees. Because the psoas attaches on the spine, it not only effects the hip and leg but also has an impact on the lower back. If the psoas is tight, this can pull the lower back forward creating an arch.

Discussing the hip flexors so far we have focused on lifting or flexing the leg toward the torso. It is important to mention that the psoas can flex or bring the trunk toward the legs as in a full sit up or roll up.

The term hamstrings and hip flexors are something that you may hear a lot in Pilates and beyond. I trust the break down of these muscle groups and how they act on the legs, hips and spine has been insightful. Next time you hear one of these terms, hopefully you will have greater appreciation for the beauty and complexity of the human body and all it does for you on a daily basis without even thinking about it.

Last September the newsletter kicked off with Anatomy 101. For back to school, we are going to revisit this topic with Anatomy 201. Our theme for the year is going to be muscle groups. Each month we will focus on a different “popular” muscle group. This month we are going to cover the hamstrings.

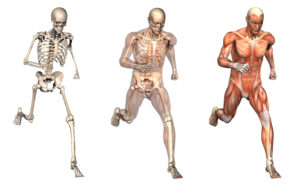

It is important to note about muscle groups, the hamstrings being a good example, that they are actually – a group of muscles. That may sound obvious but because the group name is often referred to, it can sound like it is one muscle. The general term (hamstrings) refers to multiple muscles that comprise a group.

There are three muscles in the back of thigh that make up the hamstrings. The three muscles that compose the hamstrings group are the biceps femoris, the semitendinosus and semimembranosus.

The hamstrings, all three of them, begin or have what is called their origin on the sitz bone. If you sit and put a hand underneath one hip, the bone you feel or sit on…is the sitz bone. If you practice Yamuna® Body Rolling (YBR), the sitz bone is the point that is used to begin the hamstring routine. It is also a good place to learn some of the principles of YBR as the sitz bone is one of the easier bony landmarks to find.

The biceps femoris is lateral or toward the outside of the back of the leg. It begins on the sitz bone runs along the back, outside of the leg. This muscle attaches below the knee at what is called the insertion. If you sit and bend your knee and strum your fingers along the outside edge of the back of the knee, you can feel the biceps femoris tendon as it makes its’ way to attach below the knee.

Similarly, the semitendinosus and semimembranosus are medial or run more along the inside of the back of the leg. They too attach below the knee. If you sit with your knee bent and strum along the inside back of the knee, you can feel these two tendons as they run along the back of the knee.

As the hamstrings group start at the sitz bone and run behind and attach below the knee, you can see the obvious action of the hamstrings is to bend or flex the knee. They also extend or bring the leg back at the hip joint. What may not be as obvious is how these muscles impact posture. Tight hamstrings pull on the sitz bone which pulls the pelvis down causing more of a tuck and a flat lower back posture.

Of course, tight hamstrings can make it difficult for students to sit on the floor with straight legs while keeping the back straight or when standing to reach down and touch the toes. People with tight hamstrings may try to make up for it by over rounding in their back.

All three of the muscles that comprise the hamstrings group, run from the back of the hip to the back of the knee. They impact not only knee movement but also pelvic movement and posture.

Hamstrings is a word that is often referred to but not as often given much of a detailed description. I hope defining the hamstrings has given you some clarity and insights. Please stay tuned for the continued examination into muscle groups in the next newsletter as we explore the hip flexors.

The theme for this month is balance. In the last newsletter, we saw that it takes more than muscle to have good balance and we reviewed the systems that impact balance. If you missed the article, you can find it here. For this segment, we are going to look at the most important muscles for balance and focus specifically on the core.

When it comes to daily activities and especially to athletic activities, strong arms and legs are important but you need a strong core to hold it all together. The Core is – well, the core. Even when you simply lift an arm, the abdominals are recruited to some extent. A strong core is needed otherwise movements at the hip, knee and ankle are going to be more challenging which makes balance more difficult.

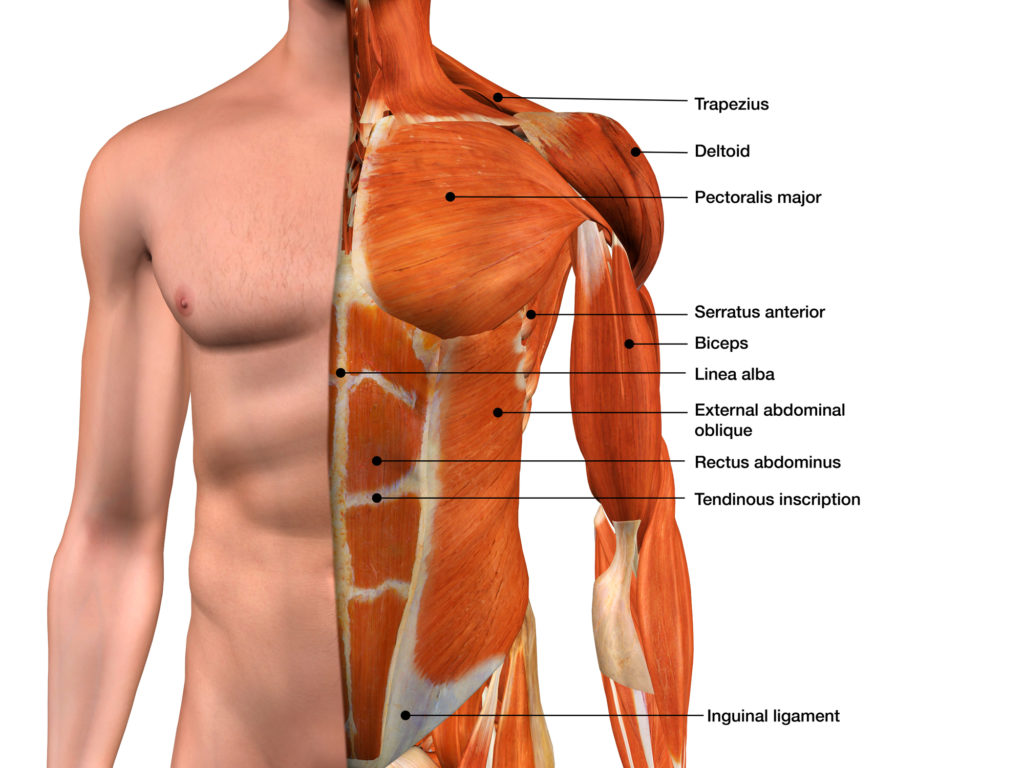

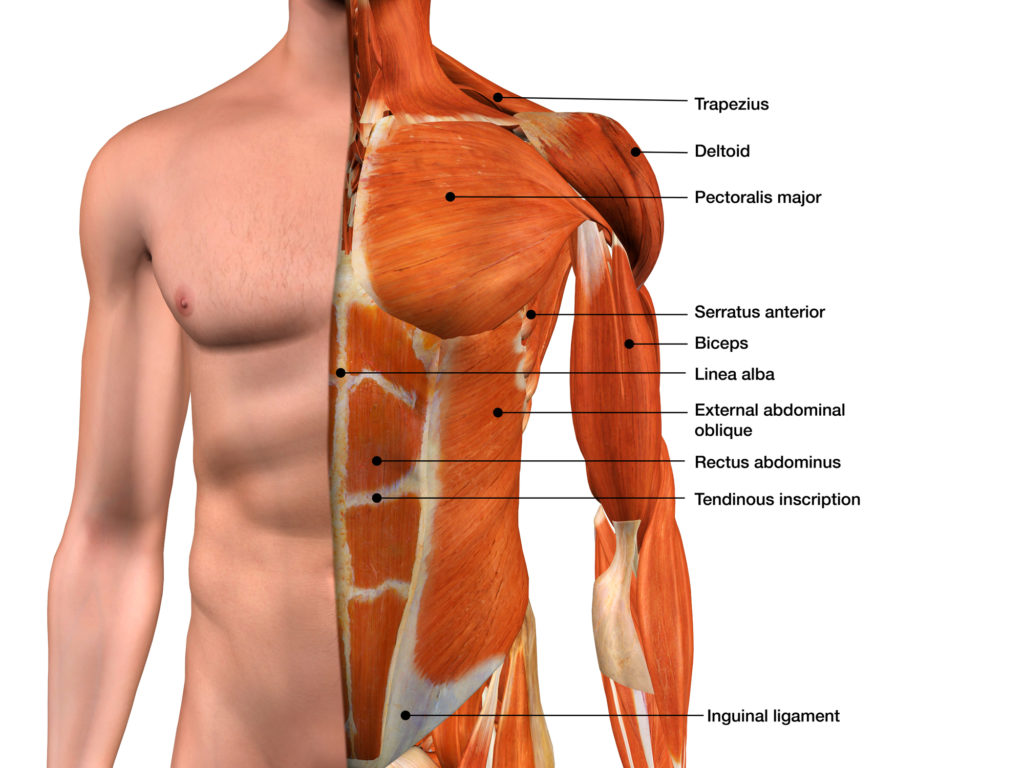

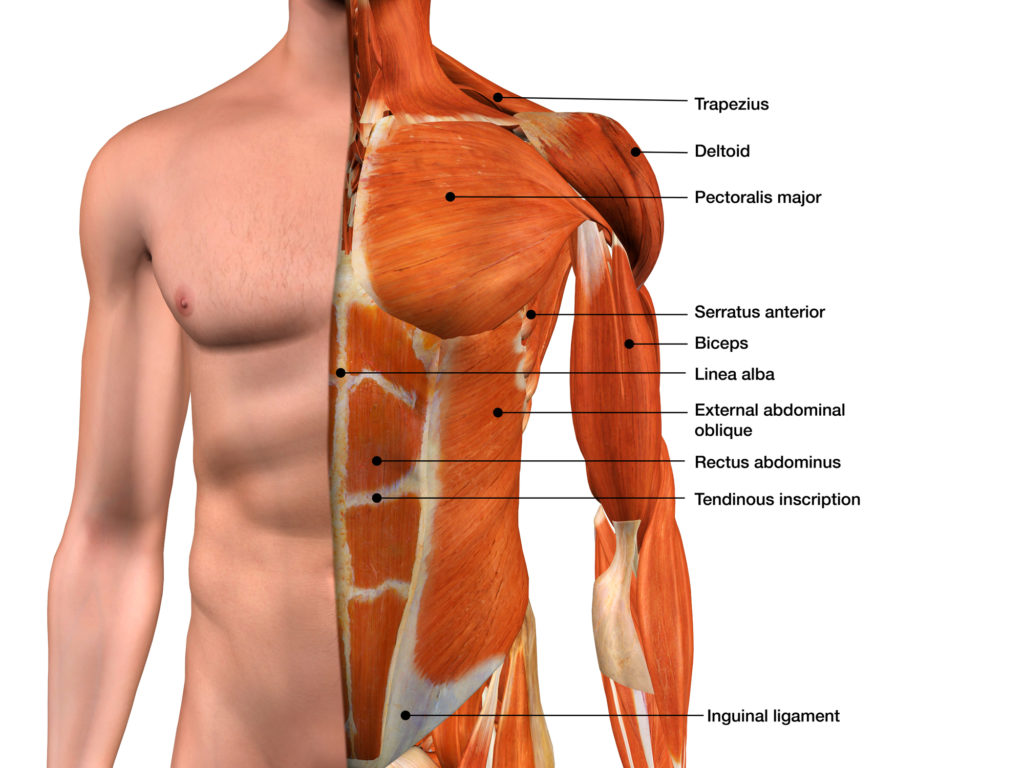

Most people think of the abdominals as the core. There are four muscles that make the abdominals group. They are the Rectus Abdominis (the six-pack), the Internal and External Obliques and the Transversus Abdominis. The muscles are layered on top of each other and the Transversus Abdominis (TA) is the deepest layer. The TA runs horizontally (like a belt) around the waistline and attaches to fascia in the back.

While the abdominals are part of the core, what may not be as widely known is that other muscles also make up the core group. Surprisingly, the Psoas muscle can be considered part of the core as it attaches on each side of the front of the spine. When thinking three dimensionally and looking not just at the front but around to the back, there are Erector Spinae muscles along each side of the spine. The Quadratus Lumborum and the Gluteals in back can also be considered part of the core.

In addition, depending on how the core is defined, muscles such as the diaphragm and pelvic floor may be included. The diaphragm is sometimes thought of as the roof to the core muscles and pelvic floor as obviously the floor to the core.

The core is central when it comes to good balance. The abdominal and erector muscles support the front and back of the spine. The psoas and the gluteals impact movement at the hips and low back. Internally, the diaphragm and pelvic floor help create stability and a deeper core connection. Multiple muscles make up the core and multiple systems coordinate together for good balance.

“Breathing is the first act of life, and the last. Our very life depends on it…. Above all, learn to breathe correctly.” ~ Joseph Pilates*

With all that is going on in the world, breathing may not seem to fall into the “above all” category. Breathing is so automatic it is sometimes taken for granted. During the daily stresses of life, breath can be held or forgotten altogether. Sometimes people wonder why breathing is important.

The respiratory rate is one of the vital signs of life and without oxygen the brain would be dead in 10 minutes. In addition to oxygenating the blood, some of the benefits of breathing are that it can help improve posture and activate core musculature.** Breathing can also assist with mental focus, stress relief and even aid those with high blood pressure.

It is true that breathing is controlled by the autonomic nervous system, so it does “automatically” regulate itself without any conscious thought. Oxygenating the blood is the primary purpose of respiration. The body beautifully calibrates itself all the time to adapt the breath to the needs of the body. All of this happens at a level with the organs and like other processes, such as digestion, occurs all on its own.

The interesting thing about the breath is that while it does operate under involuntary control, it is one of the systems of the body that can consciously be controlled. You won’t be able to mentally send a message to the stomach to digest dinner a little faster, but you do have some mind over matter when it comes to breathing.

A number of skeletal muscles are involved in respiration. The lungs do not inflate on their own. They rely on the muscles to make the movement of respiration happen. It’s as muscles contract (like the diaphragm) that a vacuum is created as the rib cage expands and air is sucked into the lungs.

Many of the muscles involved in respiration have a role in posture as well. The breath supports the posture and is also a wonderful tool in accessing the core. For example, the abdominals can be consciously engaged when exhaling. This activates the core and results in a deeper exhalation cleansing out the lungs more than if the breath were passive.

Breathing is not only a vital life function but also has other roles in emotion, expression, speaking and singing. Breathing is the bridge between the mind and body. Because the breath can consciously be controlled, the breath can be utilized to help with mental focus. While bringing us back to a more centered state, physically and mentally, breathing can help minimize some of the negative impact stress has on the body.

Breathing is a natural way to handle high blood pressure. Slow breathing sends the message that the body can come out of “fight or flight” mode. As that happens, the blood vessels widen causing things to flow more easily.

Through the hustle and bustle of the Holiday season, please take care of yourself. Consciously, set aside some time to relax. Don’t let the season pass you by and don’t forget to breathe! 🙂

*Pilates, Joseph H. and William John Miller. Return to Life Through Contrology. Pilates’ Primer: The Millennium Edition. Presentation Dynamics, republished 1998, p 12 &13.

**Fletcher Pilates Program Training Manual

Anatomy 101